A Robbery Incident Killed His Wife and Unravelled His Whole Life

June 20, 2025

Modu Bakura, a 30-year-old resident of Bama, northeastern Nigeria, was robbed in his home in 2022. His wife was killed, and he sustained several gunshot injuries that left him in the hospital for months. The single incident unravelled him. HumAngle spent eight months tracking the impact of that night on his entire life and those around him.

Charging at a man who was armed with a gun and guarded by three violent companions was a dumb decision to have taken. He didn’t know it then, but time has a way of holding past acts of folly to the light.

It was an especially unwise decision because he only had a small knife to defend himself as he launched at the man. There was no way for him to have successfully taken any of them down, but they had just shot his wife in the neck, and as she fell by his feet, blood pouring out of her while she took her last breath, Modu Bakura was overcome by a blend of incomprehensible grief and blinding rage.

He yelled, grabbed a knife from the top of his wardrobe and charged at the man who had shot his wife. They struggled until they tumbled out of the room and were now within the compound. The man’s three companions had already started to move away, having gotten the money they came for. Bakura kept screaming as he tried to slash the man with the knife he held firmly. The man shot at him, but the bullet missed him and instead pierced through the door of the room. Even then, Bakura did not relent, and so the man shot at him again, and this time, it hit him in the chin. It was then, as his clothes became drenched in his own blood and he started to feel the pain coursing through his body, that he became frightened and therefore began to think more reasonably. If he did not find a way to flee, his three children, including the six-month-old baby, would become orphans that night, he realised. He pushed the assailant away and ran to the fence that separated his house from his uncle’s, scaling it and landing in his uncle’s compound. The robber fired away at him as he fled and hit him once again in the left shoulder.

Bakura was a Point of Sale (POS) operator in Bama, northeastern Nigeria, whose job included providing cash withdrawal services. His stall once stood in Bama's main market. Since proper money machines were unavailable in the town, residents relied on operators like himself to get cash to carry out their daily activities. He usually went to the bank in Maiduguri, the capital city, to withdraw a large amount of money. When customers came to him, they inserted their cards into his portable machine to withdraw cash, and he gave them the money from his stash while charging them a small fee. The profit margin was not very high. In fact, it was very small. But he often had many customers every day, so at the end of the day, the fees culminated into a reasonable amount to keep him, his wife, and children alive. His days as a displaced person living in a camp with his family had also taught him that humans could survive on very little.

That Friday in March 2022, he had just returned from Maiduguri to get cash and had a little over ₦2 million in his possession. More than half the money was borrowed, because the business also relied on loans and investors.

It was that night, as he slept peacefully with his wife beside him, that four armed men stormed the house to rob him.

"At first, I refused to cooperate and give up the money because, like I told you, it was not even completely my money," he told me.

But his wife, whom he called Yanziye but whose official name was Fatima Mohammed, insisted that their lives were more important than the money and urged him to give it up. He eventually complied, handing over a total of ₦2.25 million ($1,400). Even then, as he gave up that money, Bakura knew that robbery was going to change his life.

He expected the attackers to leave, having gotten what they came for, but one of them lingered and very suddenly shot and killed his wife. The singular act drove him to the madness that caused him to attack the man.

It was very late in the night, but Bakura could make out the faces of the assailants who weren’t wearing any masks. He was shocked to find that he recognised two of them. One was a soldier who frequented his POS stall and sometimes even borrowed money from him with the promise of paying back at the end of the month. The other was a younger boy who used to be a member of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) — a community-based vigilante group established to help the military in the fight against Boko Haram — but was cast out because of his extrajudicial activities and high-handedness. He was notorious for his violent behaviour and his reliance on hard drugs. Bakura simply called him the ‘CJTF boy’. He could not recognise the other two. Though they all participated in the robbery, it was the CJTF boy who pulled the trigger at Bakura and his wife.

“Maybe because he saw that we had recognised him,” Bakura tells me as we sit in his father’s compound during one of our meetings in September 2024, two years after the incident.

When he landed in his uncle’s compound that night after he was shot, the man was already standing there in the middle of the compound, confused and startled, because he had heard the gunshots and the tussle from Bakura’s house.

"He was completely drenched in blood when he came to the house. I asked him what was going on, and he said thieves had invaded his house. I was so confused, I said, ‘How?’"

“He was completely drenched in blood when he came to the house,” says Modu, the uncle.

“I asked him what was going on, and he said thieves had invaded his house. I was so confused, I said, ‘How?’ It was very shocking. I asked about his wife, and he told me they had shot at her and she was most likely dead.”

Modu asked the young man to sit down, then rushed out and into the house to monitor the severity of the situation. There, he saw Yanziye unbreathing and sprawled on the floor, her blood surrounding her and spreading all over the room. While Bakura’s parents also lived nearby, he had chosen to go to his uncle’s house that night because of its accessibility from his own compound. Modu got his brother, Bakura’s father, and together they took him and Yanziye to the hospital.

The hospital, at first, refused to attend to any of them if they did not get a police report stating what had happened, and so they got it. Then, Yanziye was declared dead and Bakura was hospitalised.

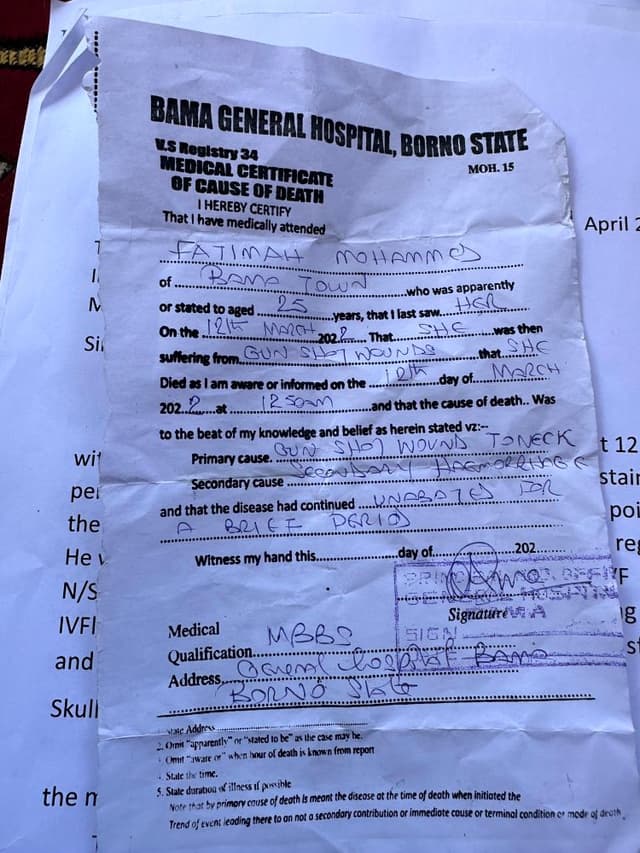

A hospital record made available to HumAngle showed that Yanziye was brought in dead that day, and the cause of death was a gunshot injury to her neck, with the secondary cause being haemorrhage, a medical term for excessive bleeding from a damaged blood vessel.

Bakura’s suspicions about the identities of the people who had robbed him were soon confirmed. The morning after the tragic incident, the news spread like wildfire. Though Bama used to be a literal war zone during the active years of the Boko Haram insurgency, things had recovered considerably in the past few years. Robbery incidents like that, especially ones that resulted in murder, were also infrequent. The CJTF came to inspect the scene and was able to recover a bullet shell. They confirmed that it belonged to an AK rifle. Bakura believes arrests were made in the days that followed.

The afternoon after the incident, one trader, Babagana Abba, sat near his place of business when the CJTF boy, who Bakura alleged had robbed him, came asking him to break down a ₦500 note. When he collected the note, he found it stained with blood. The trader, aware of the robbery of the night before and the customer’s violent history, raised an alarm about it and refused to take the money.

“I said, ‘Kai! I can’t accept this money; take it elsewhere.’ The boy claimed it was not blood but red paint. I told him I was not a child; I know blood. He left at first but came again with another naira note, but even that was bloodstained. Later, we heard that he had gone to buy alcohol with the bloodstained money,” the trader tells HumAngle.

“That young man has suffered what no one should have to suffer,” he says of Bakura in October last year. “He struggles even to feed now, talk more of sending his children to school. This is someone whose business was booming in the past. Now, he has no trade to even speak of. When he was at the hospital, we had to crowdsource to be able to raise the hospital bills. We had to send messages to the community WhatsApp groups, explaining his situation and urging people to contribute to save his life.”

Borno State has been the epicentre of insecurity in northeastern Nigeria as a result of the Boko Haram insurgency. However, with a growing deprivation, an enabling environment, and little development in communities like Bama, pockets of insecurity, like armed robbery and small-scale theft, have become frequent in recent years. Though there is no publicly available data, residents told HumAngle that the incidents have increased in the past year.

In the aftermath of violence

Bakura spent about three months at the hospital, recovering from his injuries under the less visible but more searing burden of grief and disbelief. He has one of those boyish faces incapable of darkness and despair; a smile is never too far from the corners of his lips. When he speaks of those months, those corners turn downwards, and his narration becomes characterised by long pauses in a manner typical of a person trying not to weep. His father, a poor farmer, ended up having to sell many of his possessions to foot the hospital bills during those months, he says.

His days as a POS operator had brought him close to a sense of self-sufficiency, and he had finally thought himself weaned off the kind of poverty and dehumanising hunger that being a displaced person had brought him face to face with. That single night of robbery took him back where he started.

The hospital stay was bumpy. Despite some progress with recovery, Bakura felt a persistent pain at one of the spots where he was shot. When he told the doctor this, the doctor explained that he would have to refer him to a better hospital in the capital city, Maiduguri. Bakura’s father managed to get the money together to transport him to the specialist hospital, where it was confirmed that he would need to undergo surgery. Bakura says it cost over a million naira, and raising the money was an exceedingly difficult task, but they did it.

Shortly after the incident, with neither a mother nor a father present to care for it properly, Bakura’s six-month-old baby also died. His other two children dropped out of school, and his life began to unravel like a spool of wool tossed to the floor.

In those months of hospitalisation, as he dealt with pain and the crushing financial responsibilities and debts that kept piling, he was also grieving the death of his wife.

Yanziye had been merely 25, and they had gotten married during their days as displaced people in the Dalori camp for internally displaced people in Maiduguri. They had been married for seven years. He met her, he says, at a time when he had lost faith in love. He was in the throes of heartbreak and had even gathered his things and decided to move to Ghana, away from anything that could remind him of the love he had lost. And then he met Yanziye that day in that camp. She was in the tent of one woman leader whom Bakura himself considered some sort of mentor, and he was immediately attracted to her.

“I made enquiries about her that day after we exchanged greetings, and I was told that she was single,” he says.

Bakura did not waste any time upon confirming her marital status. “I told people to ask her if she might be interested in being my wife. They spoke to her and she agreed.”

Yanziye was a calm woman. “Even when there was conflict, she liked to make peace as soon as possible. Even the community can testify to her good manners…The kids remind me of her,” Bakura says.

A debt must be paid

As Bakura struggled to sort his hospital bills and make sense of his finances, 14 other people from whom he had borrowed the money that was stolen were also trying to navigate how to get their money back from him. While they all empathised with him over the tragedy that had befallen him, they still needed their money as it was fetched from the capital for their individual trades.

Some people never asked him for the money back, assuring him that it would be fine whenever he could pay it back. But there were others who needed theirs urgently. One of them was a young man known simply as Mohammed, who was owed ₦234,000 and was very eager to get a refund. He called Bakura on the phone repeatedly and sometimes visited him at home after he returned from the hospital, but Bakura missed each deadline as the weeks passed. Sensing the growing restlessness of Mohammed and other creditors, Bakura intensified his efforts to get justice. Since the perpetrators had been arrested within 24 hours after the incident, it meant some of the money had likely been recovered from them. Bakura expected that the money would be returned to him, but that did not turn out to be the case.

He pleaded his case before several prominent people in Bama, including, at some point, the Borno State Governor, Babagana Zulum. The governor had visited Bama for some assessment work. As his convoy drove past, Bakura, now a desperate and hungry man, flung himself at the car that carried the governor, pleading for an audience.

“My scars were still fresh that time, and I explained to him everything that had happened to me. He asked me if I knew one particular man, and I said yes. He asked me to go to the man in the evening and tell him that he [the governor] asked him to bring me to him,” Bakura recounts.

When he went to see the man that evening and narrated the governor’s instruction, the man asked him to wait a bit and went back into the house. So, he waited.

“I was still waiting when I saw the man drive out in his car. I still waited for him to return. I slept there that night,” he recounts.

When the man saw him the following morning, when he woke up, he asked him to go to the chairman of the Bama Local Government Area before he would be able to take him to see the governor. If Bakura had had this information the day before, he would not have slept there that night, hoping for an outcome that, unknown to him, was not even an option, he says.

Bakura went back home that morning with nothing to show for his efforts. He planned to go see the chairman as he was told in the coming days, but first, he needed some rest and proper sleep.

By this time, Mohammed, the creditor, had reached his limits. One afternoon, he got Bakura arrested.

At first, he dragged him to members of the CJTF, but the officer in charge was a friend of Bakura’s and was well aware of how painfully tough the past year had been for him. In fact, he was the one who had donated the blood that saved Bakura’s life when he was hospitalised after the incident. He asked to be recused from the case.

Mohammed then dragged Bakura to the police station. Bakura was detained. As the days passed, his family struggled with the fact that their son, who was not a criminal but a victim, was locked up behind bars.

“He was picked up in a van here that day, like a criminal. We were all shocked and sad,” his uncle tells me.

Towards the end of his first week at the police station, he was arraigned before the magistrate court.

As they stood that day in court, the irony was not lost on Bakura that it was not the people who had robbed him that were being arraigned in court, but him, the victim, whose entire life had been upended as a result of the actions they had chosen to take that night in March 2022.

The judge who presided over the case asked to hear from Bakura. He explained his situation: the robbery he had suffered, the loss of his wife, his stay in the hospital, the death of his baby, and how all these had brought him to that point where he was no longer able to pay his debts. For a while, the judge was quiet. And then she addressed Mohammed and asked him how he wanted the court to proceed.

He said he wanted Bakura sentenced to prison for his inability to pay him back his money.

The judge then asked him if he wanted his money back, and he answered in the affirmative. She explained that putting Bakura behind bars would not guarantee him getting his money back. However, if she let him go and mandated that he pay back the money to the court in specified instalments at agreed-upon dates, Bakura would have the time to work and be able to pay off the debt. After some back and forth, Mohammed agreed, and Bakura was set free.

Mohammed told HumAngle that he understood what Bakura was going through, and that the idea of him paying the money back in piecemeals was reasonable and realistic. However, he was not willing to take the money in those small instalments.

“So, whenever the money is complete with the court, I will collect it,” he said.

After some long, painful months, Bakura was able to pay off the debt by borrowing money from other people who were not as desperate to get it back, and doing menial and farming jobs. At the end of every month, he took money to the court.

“Sometimes, my income won’t even be enough to feed my family because I was submitting everything I was making to the court,” Bukura says.

For another creditor, after many missed deadlines, he opted to take the glass-cabinet that used to function as Bakura’s stall in the Bama Main Market back when he was still a POS operator. Since the business was dead, the creditor said the cabinet was useless to Bakura. Even though Bakura had held out hope that he would one day use it again to make money, it seemed reasonable to use it to offset a more pressing issue—an outstanding debt. He gave it out. The cabinet still stands in the Bama Main Market, but it is being manned by a different person now.

As the pressure began to mount on Bakura, with creditors ringing his phone nonstop, he decided to stop answering the calls. He didn’t have any good news for any of the people who were calling him, he says, and the more he spoke to them and pleaded for more time, the more agitated they became.

During this time, he also began to hear whispers that one of the men who had robbed him, the soldier, had been freed and was seen going about his business in Bama. Two people confirmed having seen him. This reality, side by side with the inexplicable pain Bakura was experiencing, was enormous, he says.

He tried seeking an audience with the governor again. Since the last man had asked him to go to the Bama LGA chairman, he decided to start there.

“I went to meet the chairman and told him everything, so he asked me to wait, and he assured me that he would take me to see the governor once it’s time to see him. They formed various groups to meet with the governor, but I was not included as part of any group,” Bakura says.

Shortly after this, the governor drove out and was about to head somewhere, and Bakura rushed to his car once again.

“He asked the driver to stop, and he told me to wait for him, that he’d soon be back. Then I went back and sat down. After a while, the governor was back, but I couldn’t speak to him. I still had to go through someone else.”

Bakura went to a member of the constituency who had access to the governor and once again pleaded his case.

“I told him that I had gone to meet the chairman too, and that he [the member] was my last hope, and he assured me he was going to help. When it was time to meet the governor, we were all together with the member and chairman, but the police held me back at the gate. I tried to let them know I was with the chairman and the member. But both of them only turned to look at me when the police were blocking me, but did not say anything.”

Bakura says he spent two nights there by the gate, but nothing came of his efforts.

One day, as pressure mounted from the creditors and with no chance of justice, Bakura decided to flee town and not tell anyone where he was. For weeks, no one could reach him, including his parents. On the occasions when his phone rang, he would not answer. But mostly, it never even connected.

There was one particular creditor, Abubakar Muhammad, secretary of the association of POS operators in Bama, whom he owed about ₦150,000. The amount used to be as high as ₦450,000, but over the years, he was able to pay it off until it remained ₦150,000. Then, he seemed unable to cough out any more. By this time, even his kids had begun to starve. Fleeing seemed the only option to his strained mind at that time.

A few weeks after Bakura disappeared, Abubakar reached out to him over the phone and urged him to return to town.

“He told me that if it was on his account that I had left town, then I should please come back and he would never ask me for the money again until the day I could raise it and pay him back.”

True to his word, the man has not asked him to date. HumAngle spoke to him, and he explained that he himself had suffered a painful robbery incident around the same time and had lost ₦1 million. Robbers had broken into his shop and made away with the money. The experience impoverished him so badly that he ended up having to sell the only piece of land he owned to survive and get back on his feet. But it also gave him a small window into what Bakura was going through.

“The robbery could have happened to me in my house. And they might have even killed me or my wife, like they did to Bakura’s. So nobody is above misfortune. I understood what he was going through. I also told him to stop ignoring phone calls, as this would make one think that he just does not care,” Abubakar told HumAngle.

There was another woman to whom he owed about ₦200,000. This money was borrowed in the aftermath of the robbery, as he struggled to find his feet. She was the mentor in the tent where he first met Yanziye during their days as displaced people in Dalori. She has never asked him for the money back. When HumAngle spoke to her about his account, she said she was aware of the difficulties he had gone through and did not wish to pressure him.

“If he gets the money and pays me back, it’s fine,” she said. “If he doesn’t get it, it’s also fine. It’s all the same to me. He is like a son to me, and even the wife he lost was like a daughter to me. I cannot ask him to pay back that money. I would even be ashamed to. He has paid me some parts of it, but I honestly can’t even remember how much exactly; that’s how much I don’t prioritise getting the money back.”

Click to see details of Bakura's debts

HumAngle reached out to the Divisional Police Officer (DPO) of Bama to enquire about the status of the case, and he explained that the case had happened before he assumed the position in Bama, and so he was unfamiliar with it. Multiple people confirmed this to HumAngle.

HumAngle also later discovered that the case had never been brought to the Bama police station, as there were no records of it there, whether before or after the DPO assumed office.

Bakura believes that after the CJTF made the arrests, they had handed the suspects over to the army, not the police, as one of them was a soldier.

HumAngle reached out to the head of the CJTF in Bama to ask about updates on the case. He confirmed being aware of the case when it happened, but insisted that they did not make any arrests. HumAngle reached out to one of the CJTF officers, who Bakura insists had made the arrests, and he, too, denied this.

However, residents like the trader who had raised an alarm over receiving blood-stained money from one of the suspects say that arrests were made. One person HumAngle spoke to said that when the CJTF officials came searching for the ‘CJTF boy’, they had encountered him and asked about the boy.

“Three of them came that day at noon, and asked me about the boy. I was standing at the exact spot I am standing right now, and I pointed out the boy’s house to them and they went in to arrest him,” he says.

Nobody has seen the boy since, and his family has also moved from that house. HumAngle was unable to find witnesses to confirm that the other three suspects had also been arrested, beyond Bakura’s account. The man who confirmed the CJTF boy’s arrest said that was the extent of his knowledge.

These days, Bakura spends his time at the Bama Main Market. He does not yet have a stall of his own, but his cousin does, and he spends time there assisting him. They buy used phones and resell them to others. The profit margin is nearly insignificant, he says, but it is something.

“Sometimes, the profit we get on a purchase is just ₦500,” Bakura says.

In March this year, at the end of my eight-month trail of him, there has still not been much improvement in his life. Things have not gotten better. “If anything, they have gotten worse,” he says. As we speak of what changes would need to happen for his life to improve–him being able to pay off all his debts, justice being served for the murder of his wife and his own loss–a helicopter hovers above us high up in the sky, loud and all-consuming in its noise. It is the governor, I am told. He has come to observe the Friday prayers in Bama.

The helicopter quiets down as it lands, far away from where we are sitting, too many buildings and land standing in the way of our view.

After the Friday prayers, it roars again as it lifts to the sky and once again becomes visible to us, whisking the visitor away. On the ground level, Bakura looks up as it flies away.

Reporting and writing: Hauwa Shaffii Nuhu

Photos and videos: Hauwa Shaffii Nuhu

Digital layout: Shade Mary-Ann Olaoye

Animation: Akila Jibrin

Web design: Attahiru Jibrin